Saying goodbye to Gatsby: American Literature curriculum makes a change

Sophomore English curriculum looks a bit different this year: it’s missing one of the most notable books from former years.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1920’s classic The Great Gatsby, which had been on the required reading list for years, has been removed. The 10th grade English team decided to shift the focus of sophomore inquiry this year to the question “What is literature?” prompting a change in the booklist.

“The real question is not why Gatsby isn’t on the reading list this year, but rather why it was on the reading list for so long,” said Julia Callander, an English teacher and a member of the group of teachers who were in charge of making the change.

Apparently, Gatsby had been a familiar presence for such a long time that no one really knows for how many years it’s been part of the curriculum. The English department put a lot of consideration into the choice before making the decision to remove Gatsby from the curriculum, and there were numerous reasons why it was swapped out of the course.

Anne Boemler, 10th-grade English teacher and fellow member of the group who set the booklist, had a few of the grounds in mind: “We were concerned about the antisemitism in the novel; we wanted students to read texts by a more diverse collection of authors; and (you guessed it) we were indeed feeling tired of reading a hundred essays on the green light every year.”

One of the focuses of the 10th-grade curriculum, now based around the question of “What is literature?” is thinking critically about prejudice, dominant culture versus underrepresented narratives, and exploring how culture shows up in text.

While Callander agrees that looking at older texts with this lens has its value, and will be discussed in other contexts, they raised the question: “Why should our primary (or only) way of engaging in discussions about identity and power be critique?”

Boemler said that “The current English 10 teachers have all joined SPA in the last three years; we inherited a really wonderful curriculum and set of texts, but we wanted to craft a new version of the course that would draw on our own interests and specialties. ‘What is literature?’ is a question that really excites us, and that we think will help 10th graders think deeply about what they’re reading and why they’re reading it.”

As part of that pursuit to select novels that can help readers find answers to the complex question of ‘What is literature?’ Callander thinks it was time Gatsby was replaced.

“There are other equally beautiful and interesting novels that talk about the American Dream, that explore the disconnect between appearance and essence, and that use rich symbolism that teaches well,” Callendar said.

The real question is not why Gatsby isn’t on the reading list this year, but rather why it was on the reading list for so long.

— Julia Callander

Fitzgerald’s early life may have been centered in Minnesota, but his stories are often far from here, in terms of setting. There’s the connection, but a careful, self-inflicted distance as well. Nick Carraway, the narrator of The Great Gatsby describes the Midwest as ‘the ragged edge of the universe.’ Fitzgerald’s stories aren’t set in Minnesota; Minnesota is the catalyst for his characters’ behavior and greater ambitions.

The book had a special home in the upper school, as Fitgerald is an alumnus of St. Paul Academy back when it was a military school. His first short story was featured in the student newspaper at the time, the Now and Then, a detective story published when he was 13.

“The thing I, at least, really like about The Great Gatsby is the Minnesota connection,” Boemler said. “It is fun to imagine the young Fitzgerald as an SPA student, even if he didn’t stay here very long. However, we realized we could get a much more thorough Minnesota connection with another book.”

The English teachers collectively sought to explore an author’s connection to Minnesota through a more diverse viewpoint; they were looking for a work in which Minnesota is a place the narrator has a connection to, rather than a place the narrator is thankful they’ve left behind. This year, 10th graders will read Louise Erdrich’s Antelope Woman, a novel focused on one woman’s experience caught between different Native groups under the growing shadow of rising tensions between white and indigenous communities.

The sophomore English curriculum has been revised three times in three years. The course’s frame has shifted and metamorphosed; different novels have come and gone in the never-ending quest to find books that will encourage deep discussion and linger in the minds of students once the final page has been closed.

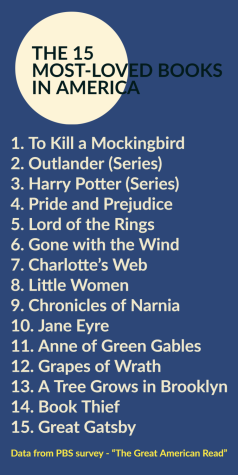

For the foreseeable future, that list won’t include Gatsby anymore.

My name is Aarushi Bahadur (she/her). I work as a Copy Editor/Promotions for The Rubicon Online. At school, I’m president of A Capella Club and am involved...

My name is Eliana Mann (she/her). I work as the Production Manager for The Rubicon online, and this is my fourth year on staff. At school, I’m a captain...