Speaking for myself: race

Like the Courageous Conversations compass implies, everyone approaches race from a different place.

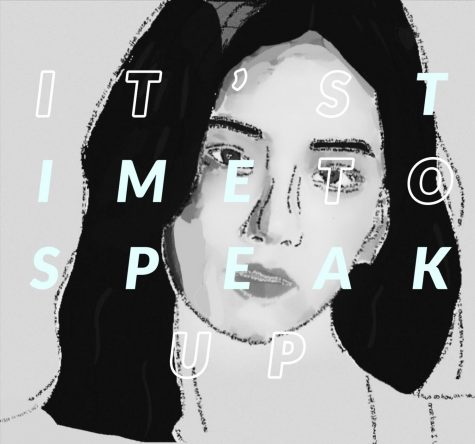

Race is not an easy thing to talk about for anyone: not for people of color, not for the white majority of America, not for the community of St. Paul Academy and Summit School. Like the Courageous Conversations compass implies, everyone approaches it from a different place. Some students of color are still learning to accept themselves, while others actively speak from secure identity. While affinity groups, guest speakers, special assemblies are valuable steps to improving the community and spreading awareness on racial injustice, individual stories of community members bridge awareness with connection to better understand and educate on a personal level. Below is a collection of student perspectives on battling racism, embracing identity and finding answers.

My struggle with race, my desire for change

Elle Chen, 11

First I must admit that I have not faced the worst of racism or microaggression. I have been shielded a lot by the small community of SPA and the attention that they have put on race in our community. I’m very thankful for that but still, I am not ready to actively call out and speak out for myself. Because even under these circumstances, I have heard things that shouldn’t have been said, things that are not all that pretty. It shouldn’t be okay but I have made it okay in my mind.

Starting from the pandemic, violent and hateful cases against Chinese Americans have surged. Just this month, an elderly Asian man was murdered on the streets of San Francisco for absolutely nothing. While these attacks are not merely covered enough, I’ve seen my Asian and white friends and community alike posting on social media, calling for justice, demanding for awareness. I’m thankful yet ashamed. I am not ashamed at them for their support but ashamed at myself for doing even less. I cannot bring myself to post anything. Not even one Instagram story, not even a word to my friends.

Surrounded by a white community, embracing my differences has not been easy. It takes immense courage, confidence and strength to digest that. I envy the people, both white and people of color, who can do so. It’s a skill I do not have but I want to have. I do not want to blame anyone for the way I am but sometimes I do wonder what I am scared of. Is it you? Or is it me?

I want to tell my story to someone and I want to make a change. But it’s frustrating when my brain and body do not agree. I want to stand up tall and proud but my legs are numb and stiff from sitting too long. I want to yell and shout but my throat is dry and cracked from underuse. I don’t exactly know why I struggle. But I know that I don’t always feel comfortable and I’m not struggling alone.

As of now, I do not have a grand story about overcoming racism or my fears of talking about race. But I am finding my answers slowly yet surely. For now, my thoughts are not sorted and my emotions are not clear but I think that’s okay. It’s okay because I have finally taken a first step. This is my first step; it’s not a pretty step but more like a wobbly first step. For now, I have at least acknowledged my embarrassment and confusion. These are the mindsets I hope to change.

My message is simple. I understand that race is not a light topic. It’s not easy for anyone. Not for you and not for me. Race is not something that can be understood with one conversation. It is not something that can be solved in a day, a year, or sometimes even a lifetime. But my message is to me and the others who are also struggling. Who will stand up for you if you do not ask for what you want? Who will know how you feel if you stay silent?

Understanding emotions, finding self-identity

Tenzin Bawa, 10

When I was younger, I used to loath going to the TAFM, the Tibetan American Foundation of Minnesota. Every Saturday morning, I would wake up and then try to sleep in as long as I could to avoid going to TAFM. In the car on the way to the community center, I would think about all the sleepovers that I missed because of the Saturday morning classes, slouch in my chair, and pout. While I was there, teachers would drone on explaining various Tibetan prayers as I would stare out a window. For a while, my peers there only viewed me as “the kid who went to a private school.” For the longest time, I disconnected my own identity as a Tibetan. I only became acquainted with a few other kids there, and I couldn’t find the value in attending the Saturday.

For the longest time, I disconnected my own identity as a Tibetan.

I started to compare my experiences at SPA to my experiences at TAFM. I would think about all the friendly, interesting teachers at SPA and compare them to the bland, strict Tibetans that would teach us seemingly irrelevant Tibetan stories. I used to think that I truly belonged with my peers at SPA, that they were the ones who could understand me best. But I slowly realized that my peers at TAFM related to me the most. My peers at TAFM also dragged on through the day, bored with whatever the teachers had to say, but they looked forward to the times they could spend with other Tibetan students. The times that we would make snow forts and have snowball fights in the parking lot, the countless games of tag and infection we would play as we dodged the cars that tried to back up into a parking spot. When I think about my own identity, I think about the memories that I made at TAFM.

How I learned self-acceptance

Katherine Bragg, 11

In the 12 years I’ve attended SPA, discovering who I am has largely been the biggest challenge I’ve faced. Although I learned so much from attending a school like SPA, I’d have to say there are many aspects of life this type of education shielded me from. I never knew the dif

ferences between myself and others until they were pointed out for me. I knew of course my heritage and why I looked different from my friends and even my own family, but I wasn’t prepared for the unsettling feeling that would come from friends and strangers jokingly pointing it out. With a white Dad and Hispanic Mom, out of the three children in my family, I was the only one who inherited Latino olive-toned skin. I’m not sure if it was SPA that failed to prepare me for life in this sense, or my own immediate family failing to warn me of the consequences of being different, but there was so much I felt I had to learn on my own. Mixed families aren’t the most common in a place like SPA, and commonly seem to be a tourist attraction for people to look at as if something they’ve never seen before. I learned from my own extended family, however, that the people who choose to point out parts of you you have no control over are the ones who aren’t normal, not you. My second cousins, who are Black Hispanic Americans, know just about everything when it comes to race and heritage and dealing with all the long explanations people ask for about why you look the way you do. Without my cousins to talk to, I don’t know how I would’ve ever come to accept my family for the way it was or understand that some people just don’t have much experience around others that don’t look like them. While my mom might be the only person in my family that “looks like me,” I don’t let the opinions of other people dictate how I view my culture anymore. Now older and proud of the parts of me that separate myself from others, I’ve embraced my change, even if others still occasionally look at me like a tourist attraction.

My time to speak, my time to shine

Rashmi Raveendran, 12

The biggest way I’ve battled with racism is not just against racist acts themselves, but more so against the gaslighting of experiences, I and others have had when people tell us the things we experience aren’t actually racist. I think this made it really hard for me to embrace my identity for a while because I felt a tug of war between many parts of my identity. I also did not fully understand the undertones of racist remarks. However, I’ve come to realize that yes – many experiences I’ve had with people have led to racist remarks that are very valid for me to be upset about. On the other hand, I also need to recognize that though I am a person of color I still have so much to do supporting black and Indigenous people in this country by spreading awareness of ways to support black and Indigenous communities, not letting my own cloud of being a person of color get in the way of helping others who face greater oppression.

Naysa Kalugdan, 10

Regarding race and ethnicity, I am a proud second-generation Asian-American immigrant. My mother is a Hmong refugee and my dad immigrated from the Philippines. Growing up, my parents always ensured to introduce me to and immerse me in Hmong and Filipino culture — and I like to believe that I have strong ties to these communities. I enjoy eating delicious Filipino and Hmong foods, learning about their history both orally and through literature, and learning bits and pieces of Tagalog and Hmong from my grandparents to educate myself and embrace my Asian heritage.

I am extremely fortunate to have a positive relationship with my family and my culture, and I never have been personally oppressed to a concerning extent. I would attribute my lack of experience with severe racism to this generation’s willingness to learn, grow, and fight for what they’re passionate about. Additionally, I would also attribute my strong relationship with my identity to my wonderful parents and their considerate teachings. I’m aware that as bilingual immigrants, my parents have faced lots of racism both in the past and to this day, but because of their horrific experiences with racial oppression, they have ensured that I understand the importance of respect for everyone and to be proud of my individualism as a Hmong-Filipino-American person.

I am a proud second-generation Asian-American immigrant.

Since the beginning of the pandemic with the outbreak of COVID, the extreme racial discrimination against those who identify as Asian-American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) has increased significantly. Noel Quintana and Vicha Ratanapakdee are two of the many who have fell prey to the disturbing hate crimes against AAPI people during the pandemic. Although the media has done a fair job at spreading awareness about AAPI discrimination, I do believe that there are more steps they could take to ensure that these hate crimes are publicized effectively. The majority of my knowledge about AAPI oppression has been through social media, but the larger, public new sources (both televised and online newspapers) could follow what many have done on social media to properly inform the public.

I have been working hard to spread awareness of AAPI discrimination to my community and my family. I volunteer for three organizations: the Philippine Minnesotan Medical Association (PMMA), the Hmong Medical Association (HMA), and I co-president and founded Kids Helping Communities (KHC) with my sister. Within these communities, I have volunteered to help these communities and to embrace my culture. One memorable voluntary action that I assisted with was when I traveled to the Philippines with the PMMA, to offer medical services to locals in rural areas who could not afford valid health care, and with KHC, to donate school supplies and toys to an orphanage fostering children with disabilities and mental health issues. With these organizations, my sister and I have been working to share the stories of Quintana and Ratanapakdee through social media and during their frequent online meetings. The health and safety of the AAPI community are extremely important to me and my family, and we strive to continue to serve as leaders and advocates for the public.

I urge those who are apart of the AAPI community and those who are allies to educate themselves on culture, on AAPI discrimination, and on ways to spread awareness and aid our community.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Just within one small community, the different experiences that everyone has with race vary dramatically. But slowly by providing safe places to share and platforms for spreading awareness, our hope is to bring everyone closer together. Race is complex and intricate. It can lead to stereotyping and injustices but it is not impossible to tackle down. Approached correctly, race can bring diversity, community and greater valuables to all. If you have a comment or story to share, make sure to leave a comment down below.

Elle Chen (she/her) is a co-Director of RubicOnline. This is her fourth year on staff. Over the summer, Elle interned at NSPA to help plan journalism conventions,...