Looking back and moving forward: celebrating 50 years of Southeast Asians in America

Zimo Xie: Welcome to RubicOnline. My name is Zimo Xie, and I’ll be your host for this podcast. 2025 marks an important year for the Southeast Asian American community, as this year marks the 50th anniversary of Southeast Asian migration to the U.S. In celebration of AANHPI heritage month this May, listen in as different generations of Southeast Asian American migrants share their families’ stories and experiences moving to the U.S.

Xie: Could you please say your name, pronouns and occupation?

Lauren LeMinh: Lauren LeMinh, I use she/her pronouns and I’m a math teacher in the Upper School.

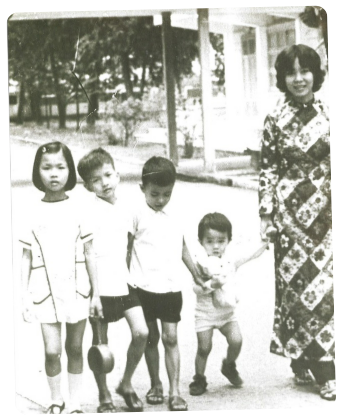

Xie: LeMinh is a third generation immigrant, and her dad was a refugee of the Vietnam War.

Xie: Firstly, can you tell me about your heritage?

LeMinh: Yeah, so I guess one of my parents, my dad, is Vietnamese, and then my mom was raised white, and I think ethnically, I feel like I was definitely raised white. And I think that comes from my dad being only five when he came over as part of the refugees from Vietnam. And so he was, like, raised white in a sense where I think my grandma was very like, ‘you’re going to assimilate and learn English’ and so for me, I feel very disconnected from kind of the Asian side, even though I still identify with it.

Xie: And then, can you tell me about your family’s history, moving to the U.S? Specifically your dad’s family?

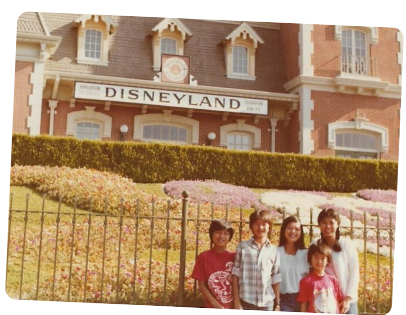

LeMinh: Yeah, so what do I remember, I don’t know a lot, just because he was five, and he doesn’t really remember much, but I just know it was right at that 1975 when everything started kind of collapsing. My grandma was able to get on like, one of the last planes over to California, where they stayed for a little bit. And then a family here in St. Paul sponsored them to come live here. And so they lived here, and then decided to stay here. And so my grandma got involved at the U, got her degree in engineering, and then went on to work for Pillsbury, and just kind of like made her family here. And so everyone in my family still goes to the U, and most of them stayed here in Minnesota. And so she got really lucky. We always talk about how it was kind of crazy that she got on the last plane out she didn’t have to- there’s always those hard stories of like, the boats and everything, and she was just like, so incredibly lucky. And she did it by herself. So it was her, and then my dad and his three siblings, and then another child that they brought over. So I think it’s really inspiring that she did it all on her own with no English, and yeah, and then she was lucky that people were willing to sponsor her.

Xie: What are your thoughts on the Southeast Asian communities being here for 50 years? And how do you feel about this year being the 50th?

LeMinh: Yeah, it’s kind of crazy to think about, I guess. I think in Minnesota here we have such a great environment for Asian people. I feel like when we moved to Wisconsin, my parents were like, looked at and weird, because most people there were white, and so when we moved back here, they were just like, super happy. And everyone, my dad was like, oh, there’s actually restaurants. There’s people I can talk to. There’s community here. And he’s really decided, even now, to start kind of getting back into learning Vietnamese, because he only knows how to speak and listen, but he can’t write and read, and so I think the community here is super welcoming, and there’s just, I feel like it’s just growing with, like, the Asia Mall. My dad’s uncle is, or cousin is actually the one that’s, like, involved with that. So we’ve like, found random relatives, like, we bought a house, or they bought a house in Brooklyn Park, and our neighbors were like, our cousins, and it was just like, I don’t know, it’s just, it’s so nice that they’re all over here, and being at the U being closer to our cousins, it just, I feel like, yeah, it’s such a great community, and you don’t get that everywhere else.

Xie: Can you tell me more about the family that sponsored you guys to move to St. Paul specifically?

LeMinh: Yeah. I mean, I don’t know a lot. I know that they kept in contact. And when she had passed away, the family, they went to her funeral and everything. They stayed super close and were super grateful. I think they were part of the church. And I think at that time, I don’t think it was like, super I don’t know. I don’t think people wanted to sponsor Vietnamese refugees. And so, yeah, I know that. I mean, I met them a couple times when I was little. I don’t know too much about them, but I just know that that was something I don’t even think I would do. It’s like. That’s a really hard thing to decide to do. But yeah, I mean, I think people still do it, and I just again, it’s hard to do. I don’t know if I would do it, even knowing that my family benefited from it. But yeah.

Xie: Are there any specific stories from your dad that he remembers from the very brief five years about the immigration to the U.S? I know you talked about them being on the planes. Were there any struggles that they went through before that, prior to that, or like adjustment coming into America?

LeMinh: I mean, I know one of the adjustments my grandma made. She had, like, a ton of siblings, and so they were very wealthy in Vietnam. So I know the transition to come here, to like, basically start over, was a big struggle. I know they face a lot of racism. My dad talks a lot about being in school, being made fun of, especially at that time, being like, one of the only Asian people, especially coming to Minnesota, I think California had a bigger population. I don’t know if I’ve really ever asked him about his time. I think he was at a refugee camp in California. I don’t know for sure, but I know they spent some time there. I know it was definitely a struggle. But I know my grandma was like, ‘We have to, you know, go to school. You have to learn English, you have to get all this done.’ So I think she was just like, she’s like, we’re gonna do it and we’re not gonna take no and we’re just gonna keep going.

Xie: How do you find yourself interacting with your family’s history and culture in your life today?

LeMinh: Yeah, I mean, I think the biggest thing is probably just through, like, food and holidays and stuff. I mean, when my grandma died, like five years ago. So I think when we lost her, we kind of lost our connection to everything, but we tried to just get together like family. But yeah, I feel again, not super connected. I just think that. I think when you move over here, a lot of times the struggle, you know, it’s to learn English, get assimilated, become American. And so I feel like we definitely lost out of that. We always joke with my dad, like, you should have talked to us in Vietnamese as kids, but he’s like, you know, I wasn’t strong in Vietnamese because he never really formally learned it. He never went to school in Vietnam. And so, yeah.

Xie: What are some of the foods you talked about that help you feel more connected to your community?

LeMinh: So we do the Lunar New Year. I know my grandma would always send us the red envelopes with a little note and a like, new penny for the year. That was kind of what she always did. It was never a lot of money, but it was always the fresh Penny. And then we would always, every summer, just because frying food is always, like smelly, we would make egg rolls in the summer. So she’d come over and we’d make like, 300 egg rolls just for ourselves, and then freeze them so that we could have them for the year. And so that was a big thing we always do. And then, yeah, a lot of it was through cooking, because my grandma was super into cooking. So we have all of her original recipes for cream puffs and curry chicken, and I’ve, like, slowly learned how to make them, but I just like, feel like you can’t always make it right. And my grandma was always super particular about rolling the egg rolls. And hers would always be perfect, and everyone else’s would be, like, long and kind of weird shaped. And so I think food was the biggest thing that we would always come together, and she’d teach us how to do things. And even, like, cream puffs, she would make them by hand, not with the stand mixer. So she’d like, get on the ground and really like, mix things up and so, but yeah, we did a lot of cooking together. It was kind of the biggest thing.

Xie: In Vietnam’s neihgboring country, Laos, the Secret war was happening at the same time.

Xie: Could you please say your name, pronouns and grade?

Lani Ngonethong: My name is Lani Ngonethong. I use she/her pronouns and I’m a junior

Xie: Ngonethong’s parents are refugees of the secret war in Laos, and she is a second generation immigrant.

Xie: Can you tell me about your family’s history of moving to the US?

Ngonethong: I’m mixed Hmong and Lao. So my parents had different journeys, but my dad was a Lao refugee. He, I believe, arrived in Hawaii in 1975. And my mom is a Hmong refugee, and she arrived in Ohio in 1975. So two very different places, and they were first a part of the first wave of Southeast Asian refugees that came to the U.S.

Xie: And what are your thoughts on the Southeast Asian communities being here for 50 years? And how do you feel about this year being the 50th?

Ngonethong: Well, I think it’s a mix of emotions, because we came here not chasing, well, my parents and many Southeast Asian refugees came here not chasing the American dream. They came here because they were forced out of their home countries. So it wasn’t as like a celebratory event as other Asian immigrants. But I think we’ve, I mean, we’ve brought so much to the community in America and around the world over 50 years, it’s been a great thing, like, for example, Minnesota. I mean, in 1975 there was only like one family here in Minnesota, but 50 years later, there’s now close to 95,000 of us. So we’ve grown so much, and we’ve also supported the American economy through farming and through just building up, like the diversity that we have in the US.

Xie: How do you engage with your heritage and what challenges or opportunities do you see in preserving it for future generations?

Ngonethong: How do I engage in my heritage? Well, there’s so many Hmong people here that it’s kind of hard not to meet other Hmong kids. And so, I mean, one thing that came out of having such a big community is you have cultural hubs like Hmong village and Hmong town, two separate places that are both in the Twin Cities, and you also have like, Hmong New Year that brings in not just Hmong Minnesotans, but Hmong people from all over California. And I feel like, to me, the Lao community isn’t as like, you know, big in the Twin Cities, but at home, I still do my own things where it’s like, we still cook food, we still use, like, cooking instruments that are from Laos. And when it’s New Year’s, we still hold the same Baci ceremonies and like we do the same customs.

Xie: How do you see the challenges or opportunities in preserving your heritage for future generations?

Ngonethong: Yeah, I guess one thing that I’m scared of, and I think a lot of people, a lot of the elders, are scared of, is that now that we’re kind of now that the generation that came here as refugees are now elderly, and they beginning to, you know, die, and now it’s up to the future generations to ensure that our cultures live on in America. One thing that I think is a big problem, which I’m a perpetrator of, is that we are forgetting how to speak our languages, like I cannot speak Hmong and I can’t speak Lao, which is a bummer, but, but that’s something I’m trying to learn. But I think, yeah, one thing is keeping that coach, like the culture of language speaking or languages alive will be a challenge, but I hope we’ll conquer it. And I guess, but one thing that I’m very hopeful for is that I think we have cultural pride now. We’re not ashamed of it. So there’s just more opportunities for cultural expression in the future. And I think like events, if not the language, lives on. I think events like Hmong New Year and Lao New Year, and like the other religious ceremonies that come with it, will continue to live on.

Xie: And how has your family’s refugee experience shaped your own identity and upbringing?

Ngonethong: Yes, my parents’ refugee experience, well, their experience is obviously different from mine. I mean, as refugees, they lived in extreme poverty, and they really had like, everything was just everything just sounded so like, new to them when they told me their stories, like, you know, there was no help really, for refugees. Like, my mom never knew what the SAT or ACT was, so she just walked in thinking it was just a regular test. But Aria and my dad, you know, there’s always funny stories, sad but funny stories of him, like living in the projects in Hawaii, and how he was bullied for not speaking English. But obviously, you know, they wouldn’t know that stuff. They were also kids too at the time, but like hearing their stories and understanding their stories of struggle and poverty in America have helped me to be a lot more empathetic. And as we see Currently, there are so many wars now in this world, and as there are more refugees and immigrants that are coming to the United States, like I’ve tried, I try to help, and I learned from my mom that, you know, to be empathetic towards them, to be patient and to understand that they’re going through something that my parents went through as well.

Xie: And my last question for you is, where do you see the Southeast Asian community in 20 years from now? And why?

LeMinh: I see it staying here. I mean, I see it growing every day. I feel like there’s more Asian companies and Asian entrepreneurs creating businesses and, yeah, I just see it getting bigger and more cohesive.

Ngonethong: I hope to really see us succeed. I think we are going to flourish.

LeMinh: I feel like we’re kind of into that more embracing our culture and being more, I don’t know, like into it like, I feel like we went through this period of like, you have to hide who you are and, you know, push it aside, and, you know, be, you know, white. But I feel like now it’s like, embrace who you are, you know, whatever kind of stuff. So I feel like it’s just gonna grow.

Ngonethong: I hope to see us really succeed. Because currently, right now, a lot of the Southeast Asians, even though we’ve been here for 50 years, a lot of us are still in the lower tax bracket. A lot of us, I think, like Laotians right now, have one of the lowest graduation rates. And so I hope in 20 years we see more Southeast Asian teenagers like me and future Gen Alpha. Southeast Asian Americans really grab onto that educational attainment and raise those numbers. You know, get our medium median household income numbers up. You know, just like, at least in those like, kind of shallow, but general aspects of success to really lift off. And in 20 years, I’m, I mean, I want to see it. I don’t know if we will, but I want to see us culturally flourish as well, and make sure that like, like I said earlier, like, you know, we we still preserve our culture and we still have our own dresses and our traditional wear, and make sure we take care of those

Xie: Awesome, thank you so much.

Ngonethong: No problem.

Xie: Thank you for tuning into this podcast. For more stories and podcasts, check out RubicOnline.

Conflict of interest disclaimer: Lani Ngonethong is RubicOnline’s In-Depth editor and Managing Editor of Diversity and Community. The decision was made to include her in this podcast due to her unique understanding on this topic and her family’s history that aligns closely to the topic of the 50th anniversary of SE Asian immigration.

Music by Grand_Project from Pixabay

This story segment was updated on May 27 to include more images.

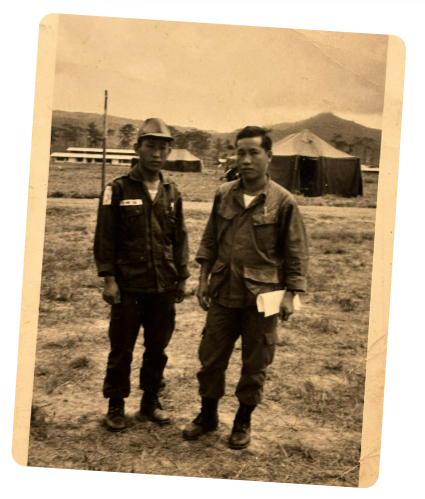

50 years ago, on April 30 1975, the Vietnam War came to an end. 20 years of fighting in Southeast Asia culminated in the capture of South Vietnam by North Vietnam, an event known as the Fall of Saigon. The war left many in Vietnam looking for a place to go. At the same time, the Khmer genocide in Cambodia and the end of the Secret War in Laos displaced even more Southeast Asians. Over the next 20 years, more than one million refugees would resettle to the United States.

Weeks after the end of the war, the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act was passed on May 23, 1975, which allowed for 130,000 Vietnamese refugees to come to America through government controlled security clearances and escape programs. The act provided welfare in the form of health, employment and education services, causing it to face backlash from conservative Americans who feared the extra resources being put into immigrants. Despite government assistance, there were still many refugees in the region that struggled to find a place to go, jumping between temporary camps in Southeast Asia. The ones who were successfully relocated still faced issues of racism and isolation.

5 years later, the Refugee Act of 1980 continued attempts to assist escapees of the war by raising the maximum number of refugees admitted from 17,400 to 50,000, as well as strengthening the already existing departments and organizations that assisted refugees. This led to an influx of Southeast Asians coming into the country, still affected by the war in the region. Xenophobic sentiments continued throughout the United States, with fears over job security and cultural assimilation grew rampant in America.

The rest of the century saw more legislation being passed dealing with immigration and refugees. 1988’s American Homecoming act gave immigration status to Vietnamese children born to American parents, allowing for an easier immigration process for Vietnamese refugees. In 2000, the Hmong Veterans Naturalization Act worked to give Hmong veterans who served in the Vietnam War a faster process towards citizenship.

In the 21st century, Southeast Asians have come to reside all across the United States, with states like California and Texas becoming the most prominent new homes. For the Hmong people in particular, Minnesota encompasses the world’s largest urban population of the Hmong in the country, with 94, 455 Hmong calling Minneapolis and St. Paul home. Recently, the state passed a bill on April 23 granting the same veteran benefits that Americans receive to Hmong veterans.

As of 2023, Southeast Asians made up 29.8% of all Asian immigrants in the United States, equalling more than 2.7 million people. Despite a relatively short history, their story as American refugees has been complex, full of facing adversity and overcoming challenges. 50 years after coming to the country, their status as citizens continues to be threatened with forceful deportations increasing under the Trump presidency. In times like these, honoring their legacy and story is more important than ever.

Additional reporting from Lani Ngonethong

Tina Tsui • May 28, 2025 at 1:27 pm

This is a great story! The podcast lets us hear the stories from the people we know in their own words. The time-line is well done too! I especially like how one of the photo captions subtly sings “This land is your land.”