The commercialization of our genome

DNA test results don’t determine identity

Identity has become a commercialized industry. With companies such as 23andMe and AncestryDNA providing convenient testing kits for about 100 dollars, thousands of people have rushed to send their own saliva to these companies’ labs in search of answers about their ancestry, ethnicity, genetic predispositions, race, and identity. Race and identity, however, are not genetic. Some ethnic groups can be identified through unique genetic expression. While ethnicity and race can overlap, however, they are not synonymous: ethnicity is a person’s cultural ancestry, while race is a social construct around people’s physical appearance and ancestry that has very real consequences of oppression. Furthermore, identity, including both race and ethnicity, is first and foremost grounded in culture, not genetics. A person’s identity consists of cultural practices, family history, sexual and gender identity, and language, to name a few. DNA results do not inherently change identity.

DNA tests should be taken as a way to explore possible ancestry or learn more information about genetic predispositions, not to change how one identifies or to gain a racial “advantage” in college admissions or job applications. DNA testing does not change who a person is or give one access to identities or cultures that they have not been raised in. If one does not experience all of the multifaceted advantages and disadvantages that a race, culture, or identity carry with them, a DNA test does not give them permission to claim that identity.

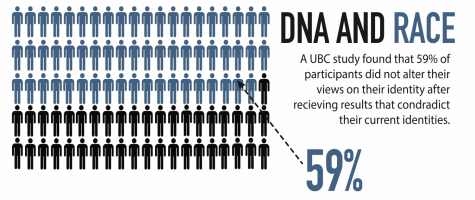

Many consumers have used DNA tests to learn more about their ancestry. However, studies have found that testing, and consumers’ reactions to their results, actually play along racial divisions. A UBC study found that 59% of participants did not alter their views on their identity and instead embraced identities that they saw positively or thought that others would be most likely to accept. One white participant, for example, continued to identify as Native American even after a DNA test result revealed that she had no Native American ancestry. The exception was among the white respondents, who were more likely to use their DNA results to change their identity.

“They were really excited to try on this identity that made them anything other than just white,” sociologist and lead author of the study Wendy Roth said in an interview with The Guardian. “It doesn’t have any consequences for them. They can try it on, mention it when it’s to their advantage and ignore it otherwise. So it doesn’t have the same consequences as race does for non-white people,” she said.

Senator Elizabeth Warren, for example, defended claiming Native American ethnicity on her college applications through a DNA test that confirmed that Warren has Native American pedigree “6-10 generations ago,” according to a document she released on Oct. 15 from geneticist Dr. Carlos D. Bustamante. These DNA results have confirmed and justified Warren’s claims to Native American ancestry to some of the public. By claiming Native American ancestry on her college application, Warren potentially benefited from her “minority status.” The Senator has not, however, embraced Native American culture or identity throughout her life and has not experienced the discrimination that many Native Americans face.

Some white consumers try to claim minority identity on the census or on college and job applications. One website called DNA Testing Adviser claims, “DNA testing can provide enlightening answers for us and our children. And in some cases that information can be used for financial gain. Proving minority status can be helpful in race-based college admissions and job applications… Others are seeking to prove their American Indian ancestry in order to share in the growing wealth of tribe casinos.” By “proving” minority status through DNA testing as DNA Testing Adviser recommends, white consumers benefit from a status that they do not actually experience for purely personal and financial gains.

On the other end of the spectrum, many white supremacists have used DNA testing to reinforce and tout their idea of racial superiority. Richard Spencer, a vocal white nationalist and supremacist, for example, tweeted that he was 99.4% European. When white supremacists are disappointed with their results they try to dispute the results or question the accuracy of the tests.

Genetics and commercial DNA testing are still evolving and improving and are by no means perfectly accurate. The pool from which DNA testing companies draw their genetics comparisons often have much more information about White Anglo-Saxon genes than, say, Aboriginal genes. Consumers should take DNA tests to learn more about their ancestry or genetic predispositions, not to search for a new identity, and results should be taken with a

grain of salt. Above all, users should keep in mind that race is not genetic, and DNA test results should not enable them to claim an identity they do not fully experience.

Lucy Sandeen is The Rubicon’s News Editor for the 2017-2018 school year. In her sophomore year, her love for writing, researching, and searching for...

Lizzie Kristal is the A&E editor on The Rubicon print staff. This is her fourth year on staff. She has kept herself busy during the stay at home order...